ABRA BELKE WAS IN LAW SCHOOL when she came across the Givling app, which calls itself “the world’s most incredible trivia game.” It promised winners payments toward their student debt.

Belke was interested. Her student loan balance was more than $100,000 and she had previously won $62,000 on the syndicated game show, “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire.”

“I’m a trivia buff,” Belke, 37, said.

However, she quickly realized it isn’t knowledge on a variety of topics that makes a player competitive on Givling. It’s money.

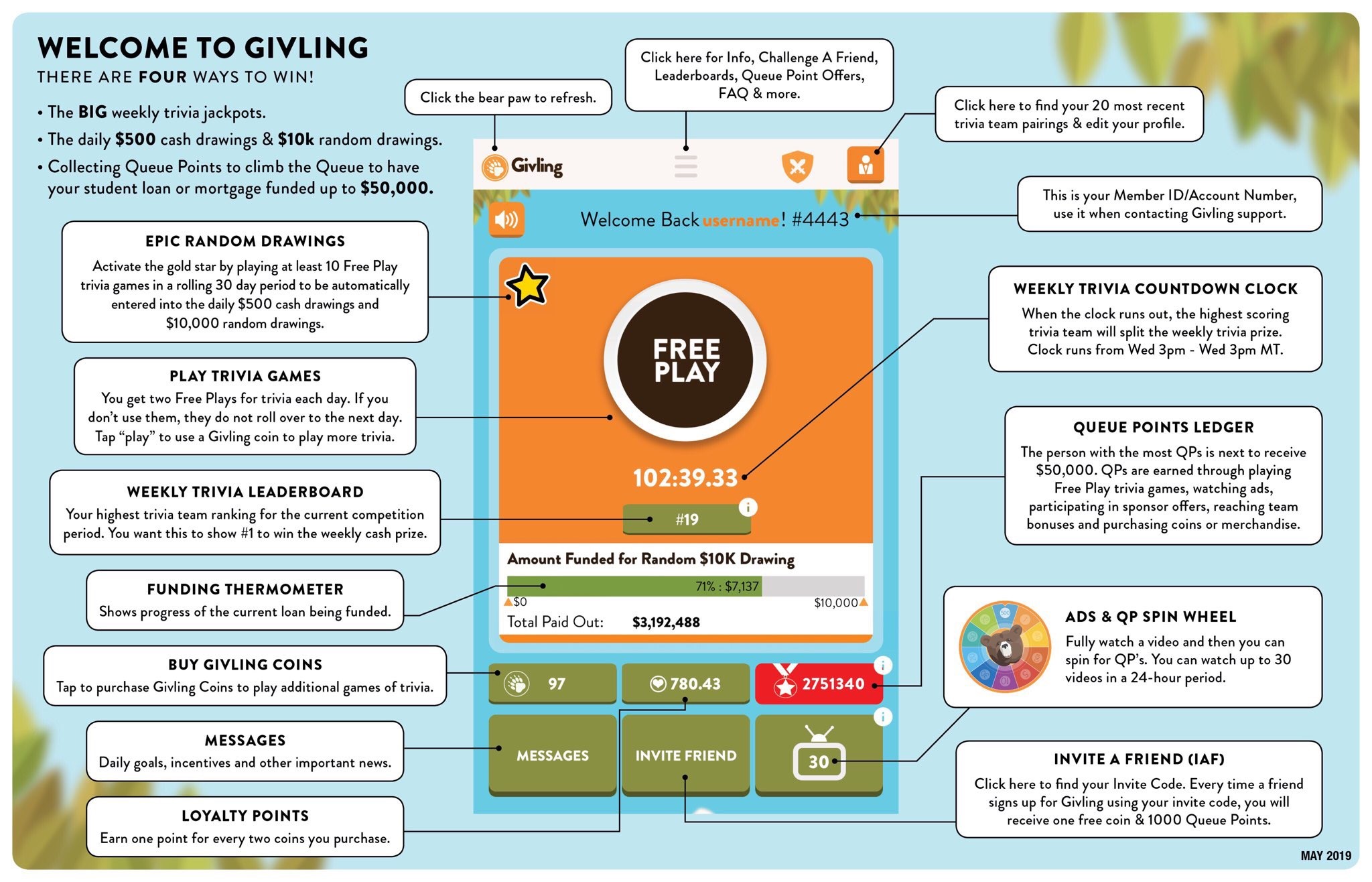

Caption/Credit: The Givling app

The app’s most-coveted $50,000 payout is awarded every seven to 10 days to players who reach first place in the game’s queue, which currently has more than 450,000 people, according to the company. To climb in that ranking, players need to accumulate queue points. That can be done by watching ads on the app, buying Givling merchandise or coins and using its paid sponsors, which include Uber Eats and eyewear maker Warby Parker.

Belke did it all. She rose up in the queue and hovered in the top few spots. Then other players would suddenly pass her. She wanted to quit but felt trapped.

Over three years, she would spend $42,000 on the game.

BILLED AS A COMMUNITY that bands together to crowdfund the payoff of people’s student debt, the Givling app has attracted a large and loyal following of borrowers hoping for financial relief.

Yet in interviews with current and former Givling players and legal experts, a darker picture emerges beyond the game’s prize wheel animations and declarations of good intentions.

People describe pouring hundreds, even thousands, of dollars into the game, though the chances of winning appear small and skewed toward those who’ve put in the most money. At least one state regulator in Minnesota found the game violated gambling law there, CNBC has learned. And legal and consumer experts point to several other red flags.

“This appears to be a pretty sophisticated scheme,” said Robert FitzPatrick, founder and president of Pyramid Scheme Alert, an international association focused on preventing fraud.

Lizbeth Pratt, founder and CEO of Givling, says that the app is the first form of “gamified crowdfunding ” and that players should not expect financial relief for themselves.

“All I did was apply crowdfunding to student loan debt,” Pratt, 60, said. “When you’re playing Givling, you’re paying off someone else’s loan. If you’re here to get your loan paid off and that’s your only reason, then you’re mad.”

However, the Givling players CNBC spoke with said they were on the app to win the $50,000 payout.

Michelle Scott, a mother of two from Wenatchee, Washington, spends around $100 a month to climb the queue on Givling. She owes $62,000 in student debt and said her monthly loan payments just go to interest.

“Givling is my main hope for getting out from under,” Scott, 35, said.

There are 450,511 registered accounts on Givling, the company says. Around 50 people have received the $50,000 payout, according to Pratt.

Stories about Givling, which have appeared in Wired, Business Insider and CNBC, have been mostly positive.

Michelle Scott, her husband Alan, daughter Rilya, and son Mason

Photo: Rebekah’s Photography

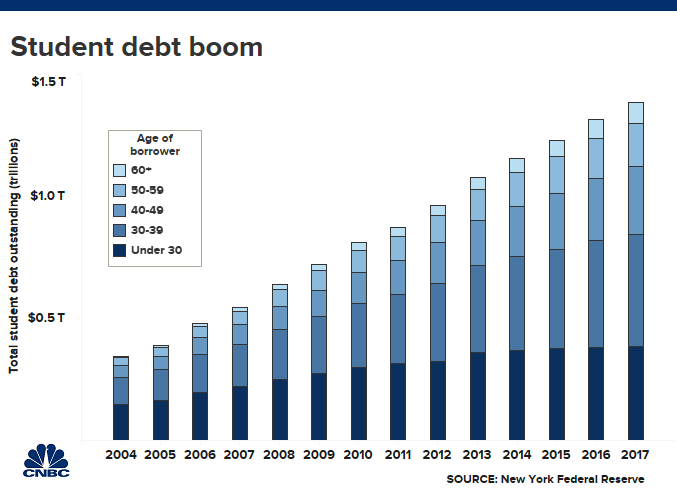

PRATT, A FORMER MERRILL LYNCH STOCK BROKER, created the Givling app in 2015, when student loans were becoming more of a problem for Americans. Outstanding education debt in the U.S. is projected to swell to $2 trillion by 2022, eclipsing credit card and auto debt. The average college graduate leaves school $30,000 in the red today, up from $10,000 in the 1990s. And 28% of student loan borrowers are in delinquency or default.

Pratt said she never had education debt. “My parents paid my way through Stanford, ” she said, “I never had to worry about money.”

Her inspiration to start Givling came from discovering people can’t discharge their student debt in normal bankruptcy proceedings, Pratt said. She filed for bankruptcy in 1990 after a divorce. “It gave me a clean state,” she said.

Pratt, who splits her time between Maine and France, said she took $1.8 million out of her retirement account to start Givling.

“I think we only brought in maybe $35,000 the first year,” Pratt said. In 2018, she said the company’s revenue was $1.9 million, a number she said it has already surpassed this year. Givling keeps 10% of the revenue, according to Pratt. The company, which is incorporated in Wyoming, now has six employees, and has given out more than $3.4 million to players, Pratt said.

“We’re on sort of turbocharge bootstrap now,” she said, adding that between 400 and 700 people sign up for the app each day.

GIVLING OFFERS frequent cash drawings and trivia prizes but most players say they’re on the app to rise to first place in the queue and secure the $50,000 payout.

To argue that a game that offers daily monetary prizes and touts itself as a path out of debt is entirely altruistic is self-serving and naive.

Abra Belke

a Givling player

One of the main ways to move up in the queue is to make purchases from Givling’s paid sponsors. If players don’t buy the products, they can lose out on queue points and drop down the list. As a result, players say they feel like hostage consumers on the app.

Belke bought many items she didn’t want or need to rise in the queue. She ordered bottles of wine, even though she doesn’t drink it. She booked hotel rooms around the country, most of which she never checked into. And she used her credit card to buy hundreds of Givling T-shirts and mugs.

“I needed the queue points,” she said. “It was obsessive.”

Last year, Belke was finally awarded the $50,000. She spent around $42,000 on the app, which means she came out $8,000 ahead, although, she said: “What it took to make it work was devastating. It takes over your life.”

And Belke might be in the red: it’s unclear if winners must pay taxes on the payout. Pratt says the $50,000 is nontaxable because it’s generated through crowdfunding and is therefore a gift. Some experts disagree.

Cheryl Metrejean, an accounting professor at The University of Mississippi who has studied the tax implications of crowdfunding, said any winnings on the Givling app are likely taxable.

“I do not believe this is actually crowdfunding, regardless of what the company chooses to call it,” Metrejean said. “This is a game where players participate, and in some cases pay, to try to win money.”

A spokesman for the IRS said the agency doesn’t offer opinions on cases it hasn’t reviewed. However, any money a player won on Givling would be nontaxable only if the people who paid into the app expected nothing in return, the IRS said.

It takes money to make money, but if it’s designed to help people that are in need then that shouldn’t be the criteria

Kurt Ricketts

a Givling player

Belke balked at Pratt’s assertion that people flocked to Givling to help others with their student loans.

“To argue that a game that offers daily monetary prizes and touts itself as a path out of debt is entirely altruistic is self-serving and naive,” she said.

“NOBODY GETS THE $50,000 without a hefty investment, ” said Kurt Ricketts, a data analyst in Seattle who has been on the Givling app since January 2018.

He owed $16,000 in student loans when he started playing. If he and his fiance won the $50,000 payout, he thought, they’d be able to sooner realize their dreams of homeownership. The winnings can also go toward a mortgage.

Ricketts watched three ads an hour on the app — another way to accumulate points and rise in the queue. “I was setting an alarm,” he said.

He subscribed to Givling’s paid sponsors, including Blue Apron and the snack company Kind. He bought Givling-stamped shirts and mugs.

“Every dollar I spent was designed to try to keep me going up in the rank,” Ricketts said. He soared up to number 160 in the queue, but then his momentum stalled. “Once you get into that top part it’s like a war,” he said.

He’s grown discouraged and plays less now.

“It takes money to make money, but if it’s designed to help people that are in need then that shouldn’t be the criteria,” Ricketts said. He estimates he spent around $1,200 on the app.

Once you get into that top part it’s like a war.

Kurt Ricketts

a Givling player

Pratt said most of the ways to win money on Givling don’t require spending money. She said many people who pay to rise in the queue are doctors and lawyers who have massive debt “but also have a big income.”

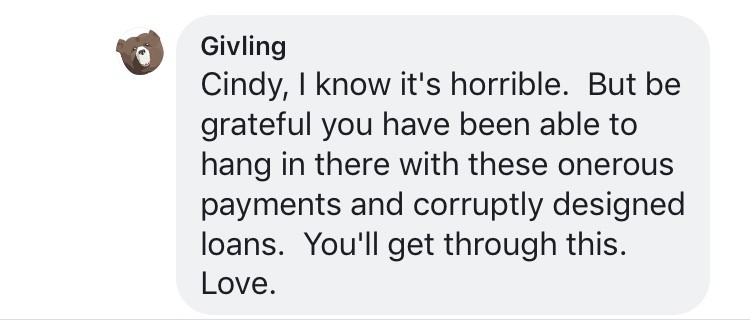

Many Givling players speak positively about the game. They say the Givling Facebook page gives them a place to commiserate with other student loan borrowers. Cynthia Thomas Reher, a veterinarian, recently won the $50,000 payout after playing for four years. “I feel more optimistic about the future now,” she said. Reher declined to say how much she spent on the app.

According to Givling, the average player pays just $6 a month. However, people can spend up to $2,500 a week on the coins that turn into queue points, and another $2,500 a week on Givling merchandise. There doesn’t appear to be many rules around how much players can spend with Givling’s paid sponsors.

, who won $50,000 on Givling in 2018, said he borrowed $20,000 from his 401(k) plan at work to play the game.

“I like to gamble,” Wilkin, 33, said. “I’m used to taking risks.”

IN MARCH 2018, A COMPLAINT triggered officials at the Minnesota Department of Public Safety to investigate Givling. Jon Anglin, an agent in the alcohol and gambling enforcement division, advised Pratt that her game was considered an illegal lottery under Minnesota law.

Givling is my main hope for getting out from under.

Michelle Scott

a Givling player

Pratt told the department she would make changes to comply with the state rules, including removing the app’s random drawings, according to a copy of Anglin’s final report obtained by CNBC.

Anglin closed the case into Givling soon after, concluding that it appears “that the game is being changed to a skill-based trivia game.”

Givling’s games might not comply with other state laws. In the app’s terms and conditions it writes that its coins for getting queue points can’t be bought by residents in Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Montana, South Carolina, South Dakota and Tennessee.

Pratt said she doesn’t know if players in those states can legally play her game. “I just don’t want to expend the lawyer fees to figure out if they can,” she said.

Givling has been “examined” by regulators in six different states, Pratt said, including California and New Jersey, but declined to give additional details. The Federal Trade Commission said it was aware of Givling but could not comment further.

STACIE BOSLEY, A PROFESSOR AT Hamline University in Minnesota who has worked with the FTC on pyramid scheme litigation, said Givling uses many of the same tactics as those schemes do to attract players and keep them engaged.

Givling constantly posts about its winners, Bosley said, but it’s not transparent about the scale of losses on the app.

“You really have a hard time assessing your chances of rising in the queue and what’s the likelihood that by taking certain actions you’re going to get a particular payout,” she said.

By framing itself as a force for good and remedy for a broken lending system, Bosley said, Givling further obscures the risk and reward trade-off players should be considering.

On Facebook, Givling describes student loans as “corruptly designed.” One Givling shirt reads: “Student loans: Don’t bear them alone. Play Givling.”

Source: Teespring.com

Suppression of criticism in another red flag, Bosley said. Givling players say the company doesn’t take pushback lightly.

In March 2019, Ricketts, the data analyst from Seattle, said he was suddenly blocked from Givling’s official Facebook group.

“I was a vocal data-driven person who would write in realistic terms occasionally,” Ricketts said.

Pratt said Givling “allows lots of negative comments.”

“But if all someone is doing is putting a negative comment on virtually every post, then we ban them for a month,” she said.

Five months later, Ricketts said he has yet to be allowed back into the official Facebook group.

Stacie Bosley

Source: Stacie Bosley

Pyramid schemes also reward people for recruiting new members, as Givling does with queue points, said FitzPatrick of Pyramid Scheme Alert. “Givling appears to transfer funds from new participants to earlier ones,” he said.

Belke, the player who put $42,000 into Givling, said players are told that the more people they get to sign up for Givling, the more people’s loans the company will be able to pay off.

“Once you get to the top, you want as many new players as possible to keep the queue moving,” she said.

Belke got more than 100 people to sign up. “It’s one of my deepest regrets,” she said.

Pratt denied that Givling targets student loan borrowers. Many apps offer prizes and reward users for bringing in new people, she said.

“A pyramid scheme is when you guarantee somebody a return on their investment,” Pratt said. “This is gamified crowdfunding. When you put money in you’re crowdfunding somebody else’s loan. Your [CNBC] investigation is laughable.”

TWO YEARS AGO, Kelly Basoco was watching the news when a report on Givling flashed across her screen.

The 55-year-old mother of five downloaded the app. She hopes to put the $50,000 payout toward the mortgage on her house in Upland, California.

By now she’s poured $15,000 into the game. She’s at 11 in the queue.

Asked how she would feel if she didn’t win, she took a long pause. “I tell myself I’ve helped other people, but I would be pretty down,” Basoco said. “I’ve put so much time and money into it and I really believe in their mission.”

Have you spent a lot of money on the Givling app? I’d like to hear from you. Please email me at [email protected]

More from Personal Finance:

Getting to know the ‘right’ people key to getting the right salary

Here are five places to retire where you can feel rich

Retirees are fleeing these 3 states in droves